IN THE NAME OF GOD, THE COMPASSIONATE, THE MERCIFUL

The Rights of Religious Minorities in Predominantly Muslim Lands: Legal Framework and a Call to Action

Introduction

In recent years, several predominantly Muslim countries have witnessed brutal atrocities inflicted upon longstanding religious minorities. These minorities have been victims of murder, enslavement, forced exile, intimidation, starvation, and other affronts to their basic human dignity. Such heinous actions have absolutely no relation whatsoever to the noble religion of Islam, regardless of the claims of the perpetrators who have used Islam’s name to justify their actions: any such aggression is a slander against God and His Messenger of Mercy s as well as a betrayal of the faith of over one billion Muslims.

At the same time, in these lands where the government’s central authority is weak, fading, or failing, the Muslim majority, in reality, is often no better off than the religious minorities. In countries where the Muslims are a majority and the authorities are aggressive, such conditions obligate the Muslim majority to protect the minorities, their religions, their places of worship, and other rights. This situation also demands that Muslim jurists, philosophers, and intellectuals engage in a serious study of the reasons for such egregious departure from normative Islam using a sound and methodical scholarship. This scholarly activity must deconstruct extremist discourse avoiding the typical responses which to date are invariably superficial, generalized, and vague condemnations on the one hand, or limited to the sphere of debates over the particularized legal proofs on the other.

Past Muslim societies were stunning examples of diversity with sundry sects, creeds, opinions, and worldviews. They all coexisted within an environment of tolerance, brotherhood, and mutual understanding of the other. History has recorded these details, and objective historians from various backgrounds have affirmed this.

It goes without saying that the Islamic tradition is based on revealed scripture, guided by the actions of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs and inspired by the noble aims of the Sacred Law. The religion’s scholars produced a vast, unprecedented cultural and legislative body of work concerning religious minorities, which have been, and which continue to be, part of the fabric of Muslim societies since Islam’s advent. Past Muslim societies were stunning examples of diversity with sundry sects, creeds, opinions, and worldviews. They all coexisted within an environment of tolerance, brotherhood, and mutual understanding of the other. History has recorded these details, and objective historians from various backgrounds have affirmed this.

In recent times, the world has experienced dramatic changes. Among the most striking of these changes involved the inhabitants of post-colonial Muslim nations adopting a new paradigm toward their minority religious communities: the contract of citizenship in which all people are equal, both in their rights and responsibilities, and with respect to their private religious affiliations, with no legal religious bias on the part of the government. Global accords, international law, and commercials systems of goods and services became a part of the local systems. These changes were instituted into the new constitutions that would become the founding documents of these nations. All of these changes are aspects of the phenomenon that is now referred to as “globalization.” It has lead to the dissipation of many of the cultural and political barriers and boundaries between societies and an increase in the phenomenon of the intermixing of ethnicities, cultures, and religions. In addition, a rise in international migration in search of economic opportunities or refuge from the fires of ethnic cleansing, religious oppression, and political exile has occurred.

Background

These radical changes beg the question: In light of these recent developments, what paradigm concerning religious minorities can the Muslim scholars, intellectuals, and philosophers advance in today’s world as an ideal goal to work toward? This paper presents the following points for consideration and scholarly discussion on this topic:

- Examination and study of the primary sources of Islamic Law, employing a methodology that is holistic—inclusive of all that it contains, bearing in mind the context of their revelation, the stipulative injunctions khitab al-wad, weighing the benefits and harms, and using the example of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs—which provides two primary modalities of relations between Muslims and communities of other faiths: one in the context of peace and another in the context of conflict, whether actual or anticipated.

- In distinguishing between the realm of legal rulings regulated by stipulative injunctions khitab al-wad, the role of context, and weighing the benefits and harms, and the realm of Islamic values and the higher objectives of Islamic Law, we find that those rulings which promote peace have both primacy and supremacy over other considerations, given that such rulings embody the core values and objectives that Islam asserts and confirm the primary mission of the Prophets: to perfect and exemplify the elevated ethics of revealed religion— values, such as the brotherhood of humanity that joins all of Prophet Adam’s offspring, the importance of mutual understanding between various peoples, the command to aid and comfort all people with virtue and piety irrespective of their religion or perspectives, the prohibition of impeding justice for those who have been wronged, and other such principles which cannot be justifiably violated by appealing to rulings with circumstantial and contingent particularities or understandings based on events that took place in a different historical context, time, and place, and involved different people, a time that had as its most identifiable trait the predominance of the culture of war.

- Medina was a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society that was not founded as the result of conquest or peaceful surrender. There, the Prophet s composed a document governing the relations between the Muslims and other religious communities that would come to be known as “the Charter of Medina.” This document was, for all intents and purposes, a just constitution that established a type of contractual citizenship. It affirmed that those who were under its authority were one, cohesive, unified polity with all of its citizens enjoying equal rights and having the same duties. This document affirmed the unity of the society in terms of religious pluralism and freedom of religion, but, despite its obvious importance, it has not garnered much study. The main reason for this is that it relates to the founding of the community and deals with a society that was, by its very nature, multi-religious—that is, one in which each segment of society freely chose its religious affiliation.

- Contemporary circumstances, including the tragic circumstances of religious minorities in some predominantly Muslim lands, highlight the need for the Charter of Medina to provide the basis for an authentic model of citizenship. This model would provide religious minorities with a new, historic, contractual status that has a basis in Islamic history. It would respect their private lives, protect their right to practice their religion, and include all citizens in the management of the society’s affairs in a manner consistent with the duties and rights as outlined in the constitution. This constitution would guarantee equality, the right to pursue happiness, the primacy of the rule of law, and provide the means to resolve political differences fairly and justly.

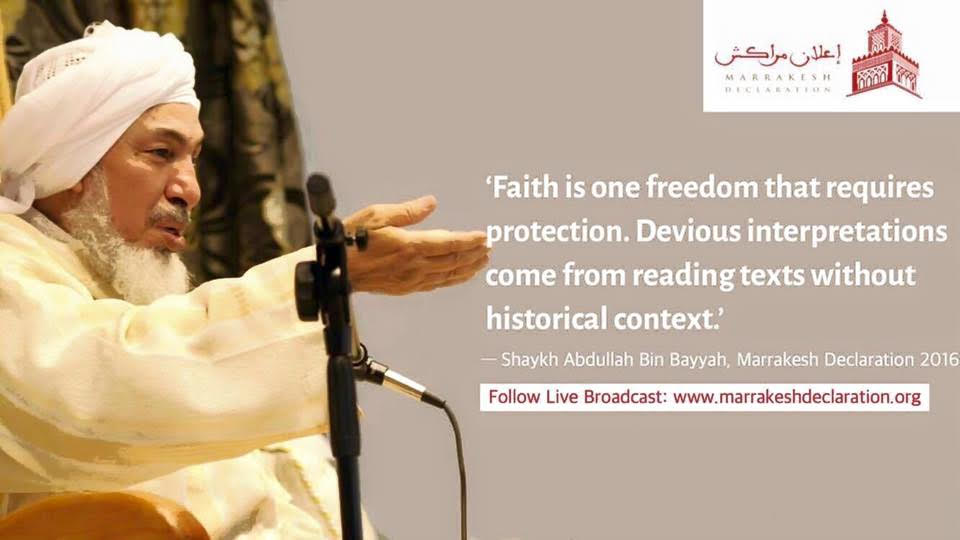

Conference

In order to examine more deeply what entails the rights of religious minorities in Muslim lands, both in theory and practice, His Highness, King Muhammad VI of Morocco, hosted a conference in Marrakesh in the Kingdom of Morocco. The Ministry of Endowments and Islamic Affairs of the Kingdom of Morocco and the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, based in the U.A.E. jointly organized the conference, from 25th – 27th January, 2016 (15th – 17th Rabi al-Thani, 1437). A large number of ministers, muftis, religious scholars, and academics from various backgrounds and schools of thought participated in this conference. Representatives from various religions, including those pertinent to the discussion, from the Muslim world and beyond, as well as representatives from various international Islamic associations and organizations were in attendance.

The conference’s discussions and research focused on the following areas:

- Grounding the discussion surrounding religious minorities in Muslim lands in Sacred Law utilizing its general principles, objectives, and adjudicative methodology;

- exploring the historical dimensions and contexts related to the issue;

- and examining the impact of domestic and international rights.

This conference, aimed to begin the historic revival of the objectives and aims of the Charter of Medina, taking into account global and international treaties and utilizing enlightening, innovative case studies that are good examples of working towards pluralism. The conference also aimed to contribute to the broader legal discourse surrounding contractual citizenship and the protection of minorities, to awaken the dynamism of Muslim societies and encourage the creation a broad-based movement of protecting religious minorities in Muslim lands.

Declaration: http://www.

marrakeshdeclaration.org/

files/Declaration-Marrakesh-Eng-27.pdfWebsite: http://marrakeshdeclaration.org

Facebook: https://www.

facebook.com/

MarrakeshDeclaration-49413932412…/…Twitter: https://twitter.com/Marrakesh2016

Instagram: https://www.

instagram.com/marrakeshdeclaration/YouTube: https://www.youtube.

com/channel/UCH7WMHg7wOqHtOhC5c_IEjQ